Fossils found by Rockwatchers

Welcome to Fabulous Finds! Here you can read about the fabulous finds found by Rockwatchers. Click on the plus sign to expand each section and discover what they’ve found.

micheles-calcite-crystals3

Thank you for sending us the photographs of your Lulworth Cove discovery. It is not a fossil as such, but has a fascinating history anyway. It is almost certainly a mass of fibrous crystals of Calcite (CaCO3) which occur at this locality in the Upper Purbeck Formation in what is called the Chief Beef Member. ‘’Beef’’ in this context refers to the layers of this fibrous calcite which has formed in between layers, along bedding planes. This was probably facilitated by some folding of the strata which allowed them to gape a little where the stress forced them apart. If the groundwater is rich in dissolved lime, then these crystals could easily have formed as the rock split apart, adding a little to each crystal as it progressed so they ended up as long, linear forms. There is one other possibility, and that is that the mineral is Gypsum, but you would need to test the rock with a dilute acid (10% HCl would be best). If it reacts, it is Calcite.

The Upper Purbeck Formation was deposited in the earliest Cretaceous around 145 million years ago, but your Beef may not necessarily have crystallised out until much later, when the folding along the Dorset coast occurred, some time in the Palaeogene Period, maybe about 50 million years ago, as a distant effect of the more intense earth movements that created the Alps, Pyrenees and Carpathian mountains.

Best wishes,

Michael

Dear Lana,

Thank you for submitting your enquiry to Rockwatch. I am glad to tell you that I know what it is!

You have picked up a nodule of Marcasite, a form of Iron Pyrites (iron sulphide, or FeS2). These are fairly abundant in the lower part of the Chalk and I note that you found it in exactly the right locality, as Child Okeford is on the edge of the Chalk scarp, where the lower layers of Chalk (termed ‘’Grey Chalk’’) crop out.

This marcasite nodule formed a short time after the contemporary Chalk deposition, at a shallow depth in the sea floor, around 100 million years ago. It was produced from the concentration of iron sulphide by bacteria living in the sediment, which obtained their oxygen from iron sulphate and converted it to iron sulphide (school chemistry!) The same process continues today in the sea and inland water where rotting vegetation creates that black, smelly mud a few centimetres down.

The nodules are invariably rust-coloured and can be smooth, or with rounded bumps or even the characteristic cubes of pyrite. I can see that yours is somewhere between the last two. If you repeat the walk, you will probably find more, particularly in newly harvested cornfields. Next time, try cracking one in half with a hammer. They frequently show beautiful radiating crystals of golden pyrite — the origin of the expression ‘’fools’ gold’’. I have often been shown these and asked if they are meteorites (which of course they are not).

I hope that this answers your question and we look forward to seeing you in the Rockwatch club.

Best wishes,

Michael

Thank you for sending us the photograph of your fossil discovery. I am pleased to tell you that your identification is correct; it is a belemnite. Judging by its size and proportions, I think that this is a piece of a fairly large Jurassic belemnite, but having been mixed up in river gravel, it is impossible to say exactly how old.

I expect you already know that belemnites are part of the internal skeleton of an extinct type of squid. This hard part, which was formed internally out of pure calcite, was at the end opposite the tentacles. They were very numerous in Jurassic seas and seem to have been the preferred food of Ichthyosaurs, one of the top marine reptile predators through the Jurassic period. On the Yorkshire coast, rafts of belemnites are often encountered, which are now thought to have been regurgitated by Ichthyosaurs in much the same way as modern owls regurgitate the indigestible bones of their prey.

Having found one Jurassic fossil in this gravel, I am sure there are more to be discovered, so good hunting.

Kind regards,

Michael

Rockwatch Ambassador, Michael shares his deductions with Piotr to help solve the mystery.

Well done for noticing this unusual rock where it certainly doesn’t belong and thank you for bringing it to Rockwatch’s notice.

Although you didn’t include a scale, the first thing I noticed was that the rock is made of quite large crystals, which will have formed from a molten magma. So it is an igneous rock. If the crystals are tiny, the rock will have cooled quickly from its molten state, like a lava at the surface. But these crystals are large, meaning it cooled slowly, allowing them time to grow big and the only place this could occur is in a magma chamber deep in the earth’s crust.

Now we come to the composition…this is more tricky as I only have photographs to help me. But I can see that the crystals have lots of parallel cleavage planes, along which they split more easily, so they are not quartz (which doesn’t cleave). The dark colour suggests a basic igneous rock (this means one which is depleted in quartz but typically contains the minerals olivine, pyroxene and plagioclase feldspar). In your example, I believe this to be predominantly a black feldspar, such as Labradorite. Does it exhibit an iridescence under certain light conditions? If so, this more or less confirms it.

How a rock like this arrived at Herne Bay, in Kent, is a mystery. But it is possible that it broke off a larger boulder, imported from SW Norway, where this type of rock is extensively quarried and some is exported to the east coast of Britain to aid in coastal defences. If you are in Kent again, have a close look at the stone revetments. They may prove to be the same.

Kind regards,

Michael

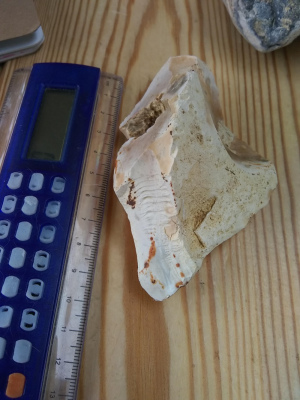

miriams-pavenham-flint-vertical-with-scale

Thank you for sending us photographs of your two objects for identification.

The paler item, which has the appearance of fish scales, is in fact a fractured flint. Flint is a cryptocrystalline form of quartz, with no preferred fracture direction. Consequently, it breaks in response to the type of stress it undergoes. This can, for example, be sudden striking force, trampling under animal hooves, frost shattering or rolling around in gravel. I am not sure which might have affected your fragment, but my suspicion is that it is an Ice Age fracture. The flint fragment is rather pale in colour, which is typical of the flint from Chalk in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. Pavenham in Bedfordshire is north of the Chalk Scarp (in which flint occurs naturally) and so the only feasible way for you to have picked up a piece there is if it was carried south in the Pleistocene Ice Sheets, around 480,000 years ago in what is called the Anglian glaciation. The stresses of both temperature and being crushed in an ice sheet must surely have been enough to cause the pattern on your flint fragment.

I have only ever seen one fossil fish encased in flint. This, an extreme rarity, preserved the bones and scales with exquisite clarity that you will agree yours does not possess.

The other specimen, with the concentric corrugation is most definitely fossil. Also in flint, it is the cast of the large Cretaceous bivalve Inoceramus, which was able to tolerate the soft chalk substrate in which it lived, by ‘’floating’’ on the soupy sea floor with its large, thin shell. The growth of flint nodules by the re-precipitation of dissolved silica sponge spicules, probably quite close to the seafloor, sometimes inundated one of these shells, enabling its preservation. In the absence or rarity of other fossils, species of Inoceramus are sometimes used to date different parts of the Chalk sequence.

I hope that answers your enquiry. Keep looking.

Kind regards,

Michael

Thanks so much! This is really interesting to know where my rocks came from! It is amazing that they are so old.

It has definitely encouraged me to keep finding rocks and fossils.

Thanks again,

Miriam

Thank you for sending in photographs of your fossil discovery from Barton. The Barton Beds are a marine mudstone deposit that was laid down in a warm sea around 40 million years ago, in the Eocene Epoch of the Paleogene Period. It was teeming with marine shellfish, one of which you have found. It is a sea-snail (or Gastropod) but without a scale and in a slightly incomplete state I cannot be absolutely sure. But I think it is Clavilithes macrospira, which is a robust shell that is not uncommon in these clay beds. Well spotted!

With kind regards,

Michael

Ben’s Carboniferous Crustacean Fossil from Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Northumberland |

Ben’s Tooth Fossil from Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Northumberland |

Ben,

I was very interested in your enquiry, and a little mystified by it. First, the rocks along the coast at Berwick upon Tweed date back to the Carboniferous, so they are probably somewhere around 350 million years old. There were fish in the seas and their teeth do turn up. But I am afraid that the photograph sent in probably does not do justice to the specimen itself and I cannot say for sure whether your tooth identification is correct or not. If you can get a really clear shot, we could have another look.

The crustacean is a completely different story, however.

I was fascinated by the images you attached and sent them on to a Carboniferous crustacean expert, Dr Neil Clark, who is Curator of Palaeontology at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. His response confirmed my intrigue:

Neil wrote:

‘’What ever the fossil is, it does not look very Carboniferous. I agree that it does look ‘prawny’ and I would need to have a closer look at it. The photos are a bit out of focus, so it is difficult to see much texture or structure, other than the possible spiny leg in side view.

What is Ben wanting to happen to the fossil? If it is Carboniferous and a crustacean, it would be a first and definitely a new species as I don’t know of any crustacean of that time that looks like that. The only spiny arthropod I know of from around that time that would look similar would be a eurypterid, but it is on the small side for one of them.

I have a slight suspicion that it may be a more modern crustacean that has been used in the mortar of a building that has crumbled onto the shore, but would need to see it to test that hypothesis. Another potential hypothesis is that it is not crustacean, but fish … but again, it would need to be looked at in detail to check that as well. Whatever the case, it is a fascinating find that would benefit from been looked at in more detail. Does Ben have a museum with a resident palaeontologist near to him? I am sure they would be happy to look at it for him if he is uncertain about sending by post’’

The exciting aspect of this is that while it could just be a bit of prawn caught up in some concrete, it could also turn out to be a really ground-breaking new discovery. It is definitely worth following up on this and I hope that you will follow Neil’s advice and let us know the outcome. Perhaps in the meantime, you could send us a few more sharp photographs, taken as carefully as possible, to show the texture of the fossil from several angles.

I look forward to the continuing story,

With kind regards,

Michael

freyas-dinosaur-bone-2

Congratulations on finding and already correctly identifying your Compton Bay beach find as a piece of Dinosaur bone, although I hope you won’t be disappointed if I cannot tell you which one. The rocks at Compton Bay date back to the Early Cretaceous, about 125 million years ago. They were deposited as stream sediments and muddy interdistributary bay infill in a vast delta complex that covered much of the southern half of what is now England, which geologists refer to as the Wealden series. Dinosaurs roamed around this flat landscape and their remains are often found, weathering out of the cliffs or as rolled pebbles after they have been incorporated in the beach sand and gravel. I am sure you know that their footprints are to be seen there as well.

The black shiny outer surface of your bone fossil is the cortex and the honeycomb texture inside (we call it Trabecular structure) is to maintain the bone strength while making it much lighter than if it were solid. The most common of the Early Cretaceous dinosaurs from the Isle of Wight is probably Iguanodon and your specimen may be one of these, although rarities also turn up.

Well spotted and look after it.

Kind regards,

Michael

Otis’s Fossil Find from Huntsman Quarry |

Goniochirus cristatus (from Stewartby Member, Callovian Stage (c. 165 million years), Woodham, Buckinghamshire, with a related Middle Jurassic (Bathonian Stage) example from Huntsmans Quarries, Gloucestershire. (centimetre scale) |

Otis,

Hello again!

Thank you for sending in your photo of the fossil found by your uncle. I have known Huntsmans Quarry for over 50 years and it has been the source of many extremely interesting finds.

The photograph is not as sharp as I should have liked, so my identification is preliminary, subject to examining an image in sharp focus, if not handling the fossil itself. But from what I can see, it looks like a fragment of crustacean claw — a small crab, lobster or a prawn.

The limestone in Huntsmans Quarry is Middle Jurassic in age — somewhere around 167 million years old. It was deposited in quite high energy conditions — there was a lot of wave action swirling the shallow seafloor around, so any shells or other objects incorporated in the soft sediment would have been rolled and abraded. Consequently, your fossil has been rounded somewhat, like a pebble.

There is a crustacean that I know quite well, in a slightly younger Jurassic deposit (the Oxford Clay). Crabs and lobsters did not change much over the millions of years during the Jurassic period, so I am suggesting that yours is related to this later one, which is called Goniochirus.

I had a look in my collection and found a few which I collected in the early 1960s. A photograph of these is shown with yours for comparison (I reduced the fossil to about 1cm as you advised). I think you will agree that they look rather similar, and I cannot think of anything else that would have this shape and external pattern.

Tell your uncle to keep an eye open for other fossils. I once saw a beautiful brown shiny Megalosaurus tooth about 5cm long from the same rock just up the road at Kineton Thorn Quarry, which a quarryman had found. I have a marine crocodile jaw from there as well. (There is just one reservation I have, about the rock — Huntsman’s Quarries used only to extract limestone, yet the piece you have looks more like sandstone, so I am just a little confused by this).

I hope this answers your question.

Kind regards

Michael

Fossilised fragment of a Brachiopod found by Oliver

Oliver,

The quarry you visited used to extract the Wenlock Limestone, which is a Silurian marine limestone which was deposited on the floor of the sea about 430 million years ago. This is really before any substantive terrestrial plants appeared on the earth; certainly before any with leaves. What you might have thought was a leaf is in fact the smaller, brachial valve of a Brachiopod, like Eospirifer radiatus, though it has been flattened somewhat during the process of fossilisation. There’s a second, but fragmentary one at the bottom of the photo. Well done for spotting it.

Kind regards,

Michael

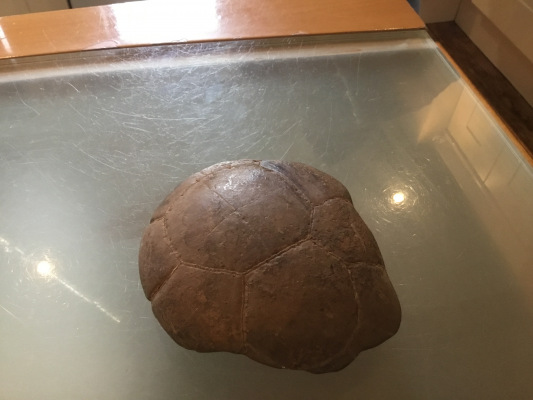

Thanks for sending me the two photographs. I can tell you about both of them: The brown pebble-like object is not actually a fossil, but is called a Septarian Concretion (or Nodule). These formed when a patch of lime concentrated around something in a mudstone sediment (often a shell) a short distance below the seafloor, during the time of deposition of the sediment. These concretions shrank internally as they hardened and small cracks formed in their interior. These filled with mineral, which in your case looks like calcite (lime). You have a very good example of a small but complete one of one of these concretions which has been slightly abraded to reveal the inner structure. Because of the way they formed, it is not unusual for a decent, uncompressed fossil to be found inside them. though it may have a “crazy paving” appearance due to the changes that occurred in the concretion as it became more indurated. The brown colouration is probably due to an iron compound, such as Iron Carbonate (Siderite) Because of their superficial resemblance, they are sometimes called Turtle Stones.

The larger pebble is probably Carboniferous Limestone, containing the disaggregated remnants of a crinoid (sea-lily). These abounded at times in the Early Carboniferous seas, some 330-350 million years ago. Although informally called “lilies”, they are actually echinoderms – related to sea urchins and starfish but were a cylindrical stem anchored to the sea floor by a holdfast which fed by waving its feathery pinnules (on top) in the sea water to catch and filter out any microscopic food particles. Look again and you’ll probably start seeing all sorts of fossils in rocks derived from the same limestone in your area.

You can find good illustrations of all these online with a simple search. I shall be pleased to send an opinion on any more from your collection. It is how I started at about the same age and nearly 60 years later I have a massive amount of material collected from all over the world. A tip for photos is to include a scale (a ruler will be ideal) and for most, 2 or 3 shots from different angles. I look forward to hearing from you and maybe meeting on one of our Rockwatch trips in Northern England once the lockdown is over. Keep up the good work.

Michael

Trigoniid fossil found in Haddenham by Aria.

Dear Aria,

I can confirm that what you have found is a fossil of a Trigoniid bivalve, quite possibly Laevetrigonia gibbosa, although there is another, more elongate variety of the genus called Myophorella, which is a little larger, more elongate and has a slightly stronger ornamentation. Without seeing the outline of the complete shell, I’d not be confident enough to suggest which it is. Modern relatives of this bivalve still thrive in the Sea of Japan. Try impressing a piece of plasticine into your fossil to get a better idea of its original appearance.

As for its age…I expect you already know it originates from the Portland Limestone, which underlies a lot of Haddenham. I used to dig up a lot of fossils of exactly the same age in my old school garden in Walton Street, Aylesbury, nearly 60 years ago. This means that your bivalve was alive some 145 million years ago, when what is now Britain enjoyed a much warmer climate than today.

If you have any further fossil enquiries, please do send them.

Kind regards,

Michael

That’s quite an unusual rock you have found. Unfortunately (or maybe not) I don’t think it is a coprolite. The Watford you refer to is, I assume, the one in Northamptonshire, near the M1 motorway. Much of this area has as its underlying bedrock a unit called the Dyrham Formation and the overlying Marlstone Rock. These date back to the early Jurassic (some 183 million years ago) when they were deposited as mud on the floor of the Jurassic sea. There is a lot of iron in these sediments and the Marlstone was actually dug for iron ore around Banbury until fairly recent times. Some of the iron came out of solution and aggregated as lumps (or nodules) of the mineral iron carbonate (siderite) just below the sea floor. I believe that your discovery may be one of these. I found a picture of something similar, in rocks of about the same age, on the Yorkshire coast

Siderite nodules in shale, Yorkshire. Credits: Ian West 2002.

The other possibility is that it is a piece of ‘’Liver Quartzite’’, a brown, really hard cemented sandstone which is abundant as pebbles in 250 million year old Triassic age desert sediments and would have been transported to Watford from the NW by a moving glacier during the Ice Age (about 450,000 years ago. If it can scratch a piece of glass, then it is Liver Quartzite.

That’s the best explanation I can offer without handling the rock myself, although your photos were very well-taken and clear.

Keep looking and you should find plenty of fossils in these Jurassic rocks.

Kind regards,

Michael